A blog entry by Dev Pandya (INSPIRE 3II3 – C01)

A critical component to understanding migration politics is examining the conditions faced by migrant workers and their broader role within national economic systems. To gain deeper insight into migrant experiences, I analyzed four hashtags related to migrant labour and the dynamics between employers, governments, and workers.

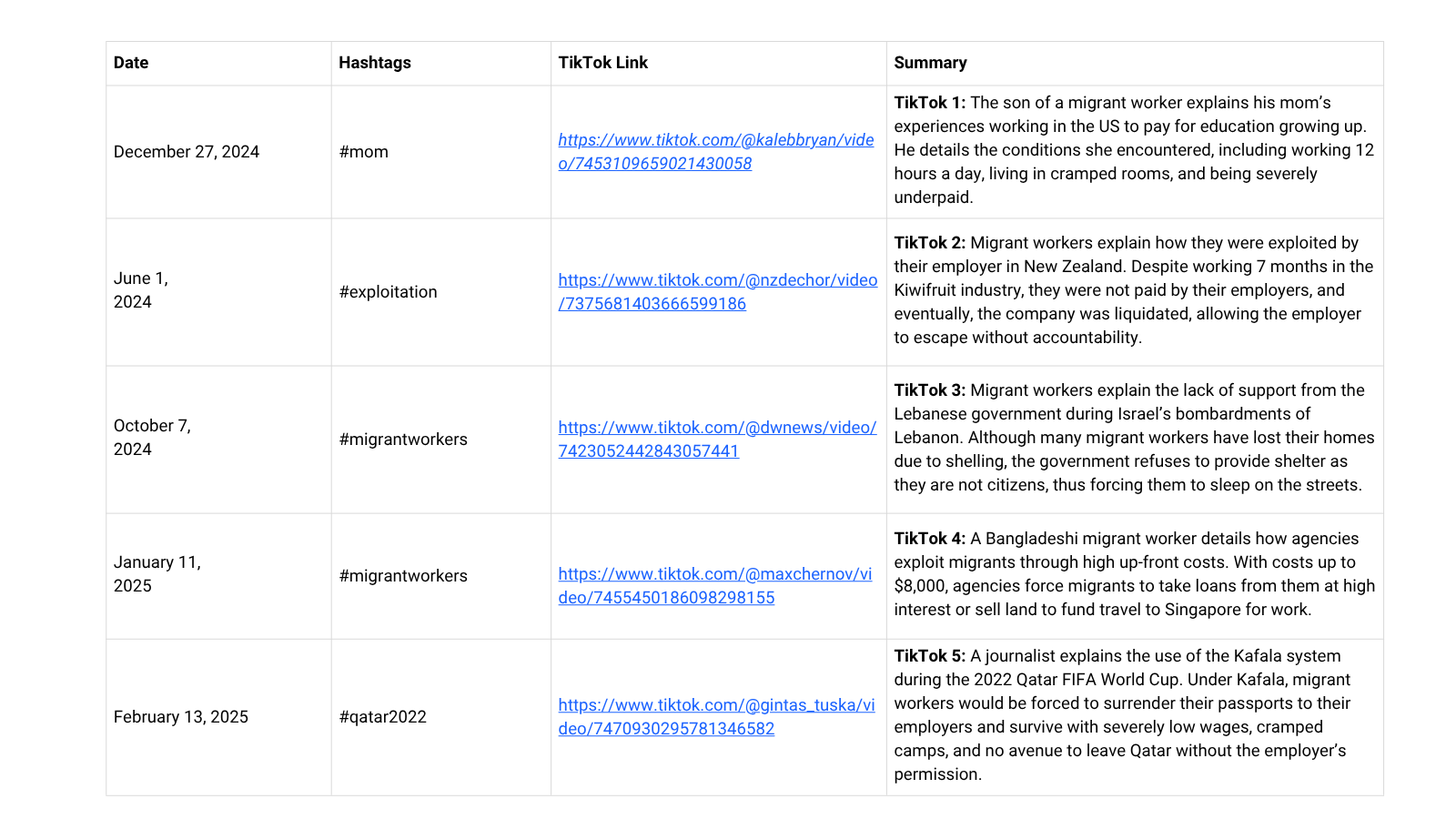

Through this exploration, I discovered five TikToks that exposed uncomfortable realities about the migration worker experience, including exploitation by employers and government systems.

A recurring theme in TikToks 1, 2 and 4 was the financial exploitation of migrant workers by employers and recruitment agencies. In TikTok 4, a Bangladeshi migrant worker describes how migration agencies specifically target low-income communities, persuading young men to pursue overseas employment with promises of high wages. However, these agencies often impose exorbitant fees for facilitating migration and employment, forcing families to sell land or take out high-interest loans, sometimes from the agencies themselves. As a result, much of the income earned abroad goes directly toward repaying these debts, leaving workers with minimal earnings and, in many cases, in a worse financial position than before they migrated. Driven by the opportunity to lift their families out of poverty, though, many accept these offers despite the risks.

The comments under the video reveal that this experience is far from isolated. Many migrants share similar stories of low take-home pay and predatory practices by agencies. Due to language barriers and the foreign environment, migrants often do not understand the rights they are entitled to and how to appropriately advocate for themselves. This vulnerability is compounded by rhetoric promoted by agencies that frame them and their partner employers as angel-like saviours offering life-changing opportunities to the poor—in return, expecting unquestioning obedience from migrants. This dynamic fosters a toxic work environment where migrant workers possess no control over their wages, working hours, or conditions. As a result, stripping them of their agency and reinforcing cycles of exploitation.

Unfortunately, there appear to be few mechanisms in place to hold exploitative companies accountable and safeguard the rights of migrant workers. This lack of oversight is especially evident in TikToks 3 and 5, where migrants describe being placed in unsafe and inhumane conditions due to government inaction and weak regulatory frameworks. In TikTok 3, for instance, migrant workers recount their experiences during Israel’s bombardment of Lebanon. Displaced and left without shelter, they received no assistance from the Lebanese government to return home or access emergency housing. Because they were not citizens, the state refused to provide support, effectively abandoning them in a conflict zone and putting their lives at risk.

Similarly, TikTok 5 features a journalist detailing the treatment of migrant workers in Qatar for the FIFA World Cup. Under the Kafala system, employers confiscated workers’ passports, preventing them from leaving until their contracts were fulfilled. This created a severe power imbalance, where workers were forced to work in extreme heat without the ability to advocate for better conditions—fearing they would never recover their documents and return home. The absence of strong legal protections and enforcement mechanisms allows such abuses to persist unchecked. In many cases, employers serve as both landlords and supervisors, giving them disproportionate control over workers’ lives. This dual role enables them to suppress complaints and perpetuate harassment, exploitation, and human rights violations with little fear of consequences (Caxaj & Weiler, 2024). Critically, this pattern of abuse is not confined to the Middle East or South Asia, but rather a global issue that requires urgent reform.

Neoliberal policies have increasingly led governments to grant corporations greater freedom to operate with minimal regulation, often prioritizing profit over worker welfare. Migrant workers, in particular, have become ideal labour sources under this system due to the disproportionate power companies hold over them and the lack of governmental oversight. As former migrant worker Gabriel Allahdua shared on CBC’s Windsor Morning, the structure of employment migration is deliberately designed to minimize worker agency while maximizing employer control. This imbalance allows employers to dictate nearly every aspect of a worker’s life—from their movements and meals to their working hours (Caxaj & Weiler, 2024). Due to absolute control, migrants are unable to speak out, fearing retaliation or the loss of future employment opportunities. Programs set up by federal governments, such as the Seasonal Agricultural Work Program (SAWP), benefit from this inequitable power dynamic by being able to import low-cost labour to meet seasonal demands without being held accountable for the well-being of those workers, since their voices are usually silenced by fear. Since these jobs are typically undesirable to local populations, the arrangement benefits both employers—who secure a compliant workforce—and governments—by addressing labour gaps (Caxaj & Weiler, 2024).

This cycle of systemic inequity and exploitation will only continue unless governments intervene with strong legislative reforms. To ensure fair treatment, governments must consult with migrant workers and implement policies that guarantee and enforce equal rights for all workers, regardless of immigration status. Furthermore, by reducing the power employers hold through the creation of independent bodies responsible for arranging migrant housing, migrant workers can protect their agency and advocate for better working conditions without fear of becoming homeless or unfairly targeted. Although migrant workers are not permanent residents of their host nation, they should be entitled to the same rights that all workers do—by transitioning the current top-down power dynamic into a bottom-up system, we can achieve this.

Overall, exploring this side of TikTok was a really insightful experience in understanding the treatment of migrant workers internationally. It provided meaningful perspectives on exploitation done by abusive employers and the complicity of governments, while also exposing the lack of legal frameworks meant to protect migrants. By confronting these inequitable power structures within migration, migrant workers can contribute meaningfully to foreign economies while maintaining their agency.

References

Allahdua, G. (2025, February 27). Former Leamington migrant worker sharing his story in a book, and Sarnia library talk [Interview]. In CBC’s Windsor Morning with Amy Dodge. https://www.cbc.ca/listen/live-radio/1-106-windsor-morning/clip/16130772-former-leamington-migrant-worker-sharing-story-book-sarnia.

Caxaj, C. S., & Weiler, A. (2024). “You’re Just Stuck in a Hole, Really”: Mechanisms of Structural Racism Through Migrant Agricultural Worker Housing in Canada. Qualitative Health Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/10497323241285768